Diagnosis

An excerpt from The Ben Book: A Father’s Memoir appears below, with the author’s permission. Details on where to buy the memoir are available at the bottom of the page.

It is January 1986, and we have just arrived back in Sydney from a holiday in Tasmania. What I thought was to be a routine visit to a paediatrician was in the diary for the next day. I didn’t give a second’s thought to that approaching doctor’s appointment at any time while in Tasmania. Benji was a delightful, placid baby boy. From day one, he had been a peaceful and calm baby. However, despite appearing normal in every way, an alert community nurse at the local child care centre had noted what was not obvious to his parents or anyone else – that he was just a little bit slower than normal in his physical development – and had recommended some routine blood tests a month earlier.

It is January 1986, and we have just arrived back in Sydney from a holiday in Tasmania. What I thought was to be a routine visit to a paediatrician was in the diary for the next day. I didn’t give a second’s thought to that approaching doctor’s appointment at any time while in Tasmania. Benji was a delightful, placid baby boy. From day one, he had been a peaceful and calm baby. However, despite appearing normal in every way, an alert community nurse at the local child care centre had noted what was not obvious to his parents or anyone else – that he was just a little bit slower than normal in his physical development – and had recommended some routine blood tests a month earlier.

I remember answering the phone an hour or so after getting back from the airport. It was the doctor’s secretary, ringing to confirm that we had not forgotten the appointment, and wanting to make doubly sure that we were going to keep it. As I put the phone down, it struck me even then that such a phone call was a little out of the ordinary. It made complete sense to me 24 hours later. The doctor knew the news that he was to deliver: that the results of the routine blood test pointed to the high likelihood that Benji had Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD). The first question he would have seen coming from the stunned mother and father sitting in front of him, a little boy on their knees: Muscular Dystrophy – what on earth is that? Surely there must be some mistake?

(Now, many years later, those few minutes just before the announcement that changed everything have also stayed with me. I understand that trauma etches itself into the brain; but does it also work retrospectively? Freezing in time the ‘just before,’ the last moments of normalcy, as well as the shock itself? Sitting, relaxed, in the waiting room for the doctor that morning, those last minutes are as vivid as the diagnosis moment itself).

We stumbled out of his office. Fifteen minutes earlier, we had been watching Benji playing on the floor with the toys in the waiting room. Now a whole series of medical wheels had been set in motion, in tandem with the knowledge that, not only had he just been given a fatal prognosis, but that a life of wheelchairs and other unimagined challenges lay ahead for him, and for us.

It was a couple of weeks before I was able to face my colleagues at work. My boss came into my office on my first day back, and did his best to console me with some of the sadnesses that had happened when he was a young father. Leaning forward in my chair while he talked, unable to look him in the eye, a slow drip of tears formed a tiny wet patch near my shoes on the office carpet.

Before that day back on campus, much had happened. Benji had been operated on; muscle tissue had been taken out of his arm and leg (the post-mortem in Adelaide 21 years later noted the old scar on his left arm but not the one on his left thigh); the results had proven conclusive for DMD; a new world order had begun. The muscle biopsy operation took place in the Children’s Hospital at Randwick, NSW. That particular hot summer afternoon seemed as if it would never end. The western sun shone fiercely through the curtains of the infants’ ward. The specialist was Dr Graham Morgan, a man who had devoted most of his professional life to those with this disease. Dr Morgan came into the ward to see us just as Benji was waking up from the anaesthetic. Apart from confirming the grim diagnosis, he said little. But he spent a long, long time, at least an hour, with us, just standing there, next to Benji’s cot.

Dr Morgan reminds me now of the way T S Eliot describes the figure of Tiresias:

“I Tiresias, old man with wrinkled dugs

Perceived the scene, and foretold the rest –

(And I Tiresias have foresuffered all

Enacted on this same divan or bed;

I who have sat by Thebes below the wall

And walked among the lowest of the dead.)”

I have often wondered how a busy specialist holding a senior position in a major hospital would or could choose to spend so long with us that day, as if there was nothing else on his mind except this apparently normal little boy starting to stir in his hospital cot. I think I understand it better now, having lived through Benjamin’s life cycle from beginning to end, and feeling like Tiresias myself when I meet newly diagnosed young boys for the first time. Dr Morgan knew the full span of Benji’s life-to-be, and he knew our future too. He had perceived and foresuffered this scene many times before, and could foretell the rest. Compared to him, we knew nothing about what life now had in store for us. He stood there with us for so long, because this fearful knowledge weighed on his shoulders, weighed him down. A dreadful truth had been confirmed, including the death of a dream about a happy and normal future for this family. In the face of such knowledge, what humane and honourable man would not just stand there for a time, in silent solidarity with a mother and father who are still too shocked to be fully grief-stricken?

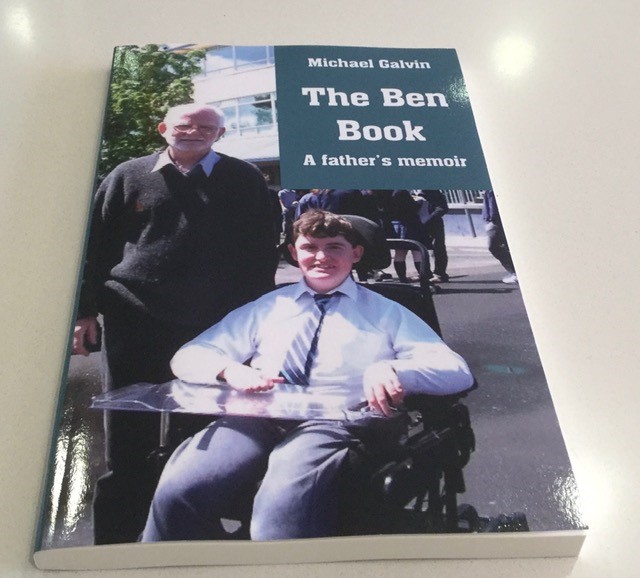

Title: The Ben Book: A Father’s Memoir

Publisher: Ginninderra Press, Port Adelaide, 2020

It is available as a paperback, from the Store on the publisher’s website: www.ginninderrapress.com.au

It is also available on as an e-book on Amazon Kindle.